When I started writing this story in November, it was just another assignment for class. I planned on turning in the required 750 words and hoped for a good grade.

But over the next few weeks, the story began to reveal its depth through sources who wouldn’t talk to me and fading documents that barely could.

On a Thursday, I went to the agriculture and environmental science Chapel. Walking into their classroom on the bottom floor of the Hardin Administration Building, I knew I had entered a crowd I didn’t belong in, but at the same time, they made everyone there feel welcome.

I was trying to meet the professors and the students in the department, hoping to write a little feature about the ACU farm or maybe the rodeo, but as soon as I mentioned the Optimist, no one wanted to talk to me. Not an uncommon experience.

But what I wasn’t aware of was that over the past few days, hard decisions had been made behind closed doors. I didn’t know the group I had targeted that morning was actually a single, living, breathing organism – with more than 70 years of history – that was about to be targeted by the very university they belonged to.

The reason they couldn’t talk wasn’t because they didn’t want to. It was because they were told not to.

I was seen as a nosy reporter, trying to break the news they knew was coming. All the while, I was entirely unaware. There was a meeting scheduled the next Wednesday between the provost and AES students to make the announcement about the proposal to restructure. Understandably, they didn’t want the Optimist to break the news before they could tell their students.

By the time I realized what was happening, I still needed a story to turn in for a grade, and still, no faculty or administrator would talk to me. That’s when I turned to the history.

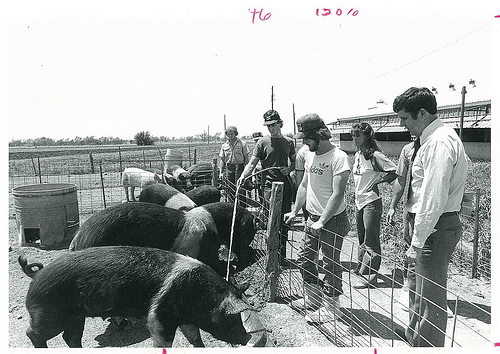

I dug through seven decades worth of newspaper clippings and photo archives about the department. I saw every story ever published about every stock show, new tractor and rodeo queen.

I visited Rhoden Farm. I played with the farm dog. I talked to students about their classes and their animals and their quail-tagging project, and everything but the future of the department that had yet to be announced.

The story began to tell itself. I didn’t have to have quotes from the ones living it to see what was happening. The future of the department and the consequences of its closure began to become clear. This story was already over 1,200 words long before I even conducted a single interview about the news.

This department has built a heritage and culture unlike any other department on campus. These students care about their vocation almost as much as they care about each other.

Ag didn’t need me to write their story. They’ve been writing it for 71 years. I’m just the one who got to publish it.

Read the full feature here