BY: LONDYN GRAY

“Number 18, you look like you don’t shower!”

I chuckled and shrugged it off.

“Londyn!” They had looked up the roster. “Do you even brush your teeth?”

I laughed again, rolled my eyes, and continued watching the game from the sideline. We were playing the University of Florida on its home court.

The volleyball powerhouse earned the right to strut into warmups, and its fans’ smug remarks were seemingly warranted, but completely unnecessary. The University of Georgia was going to lose, and Florida was going to win again.

Why was their student section targeting an injured bench warmer like me? Easy prey.

Playing environments are crucial to the game. ACU volleyball’s head coach, Alisa Blair, was an assistant at Stephen F. Austin last year. Its court is rightfully regarded as “the pressure cooker.” It’s suffocatingly hot and forcibly loud.

It’s not a fun place to play – unless you’re SFA. Blair said the win over Rice in 2019 (right before Rice beat No. 3 Texas) was because of the noise created by the student section. Crowds can make the difference.

Opponents playing the Texas A&M football team on its turf are notorious for snapping the ball too early or having too many people on the field because of the sheer roar of the “12th Man.”

In indoor sports, this environment is more personal. The crowd and the bench are feet apart, with no railings to keep distance, and no face masks to hide behind. The indoor athlete is vulnerable, and the student section knows it.

When the men’s basketball team played at Grand Canyon University, the GCU student section was given profiles of targeted players. The profile said things like “#12 Mahki Morris: Can’t travel without his stuffed animal,” and “#23 Airion Simmons: Refers to himself as Big Jelly. Decent scorer, but can’t stay in for too long (nickname is Big Jelly after all).”

While the flyer might be extreme, this strategic attack is not uncommon to student athletes. Athletes face personalized heckling as early as high school.

But athletes might be the worst hecklers of all.

For the home team, heckling is fun. Athletes know the thrill of playing for a cheering crowd that has made your competitor their own. Fans help puff up your chest and loosen the tension of competition.

ACU student athletes are encouraged to attend each other’s “purple games,” and it’s implied that our presence should be known. To both teams. Heckling is expected, and to some degree, it’s fully dismissible.

At its best, heckling makes the game more fun for the home team. At its worst, heckling is endorsed bullying. It can dehumanize the athlete, diminishing them to a pawn of entertainment.

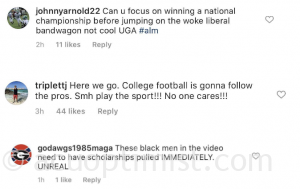

In the summer of 2020, Georgia football, a primarily Black team, posted a Black Lives Matter video on Instagram. The post was raided by disapproval:

My friend on the team, a Black man, was in hurt disbelief. Outcries against racially motivated violence were told to shut up for the sake of playing a game.

This is the overgrown weed of heckling. It’s rooted in the perceived space between the athlete and the rest of their being.

Maybe it’s the Christian values, or the underwhelming size of the student section, but something keeps ACU from planting this seed.

Maybe we just don’t care enough. But if we do start caring, and if we become the loudest fans in the WAC, let’s stick to supportive cheering.

Remember that what you wouldn’t say to a classmate, you probably shouldn’t yell from the stands. And just don’t ever tell the injured benchwarmer she looks like she smells bad.