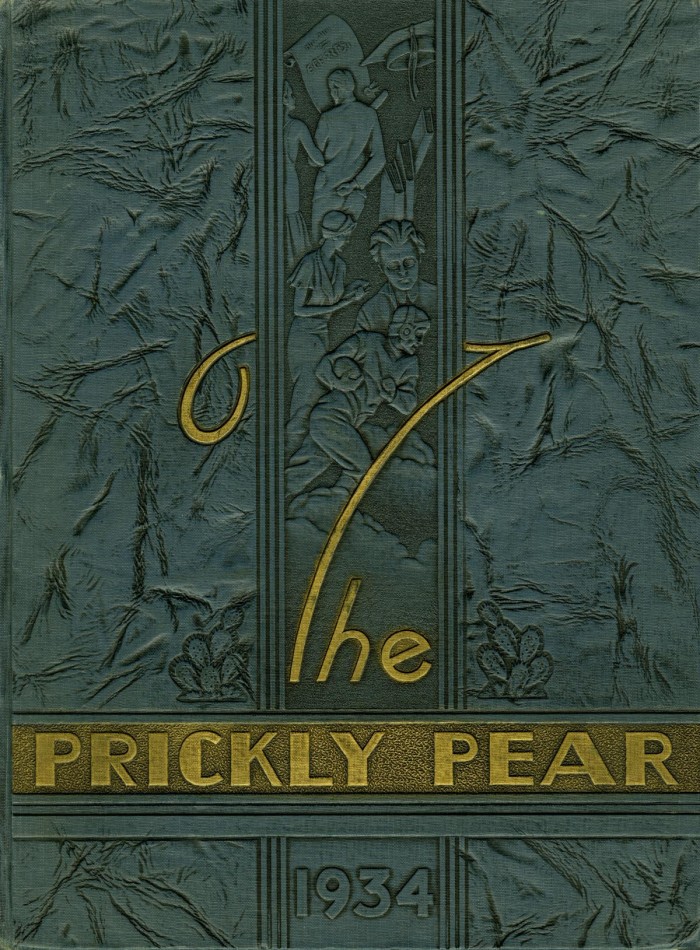

The last Prickly Pear, the former university yearbook, came out in 2008 and ever since the yearbook hasn’t been back. That could change if Julia Kennedy, sophomore English major from Lubbock, is able to get people on campus to support her bill.

Kennedy said as sophomore class president she presented a resolution to congress to bring back the Prickly Pear because “students [would] benefit from having a yearbook to look back from, and it was wonderful worthwhile tradition, and a great memory for ACU alumni and no longer doing it partially disconnects us from our old members of ACU,” and congress was on board but now she has to get people to support it.

Kennedy said although she is in the beginning stages of the bill, she is talking to administration and might send out a campus vote through email, because she wants “to know if people want it and appreciate it.” After the vote, depending on the results, the bill will pass only if students agree with her bill.

However, an annual yearbook isn’t easy to produce, according to those who have worked with the Prickly Pear in the past. There needs to be financial support and full commitment year round.

Cheryl Bacon, chair of the Department of Journalism and Mass Communication, worked for the Prickly Pear for 27 years as a student on staff, assistant advisor and then as a faculty advisor. Bacon was the one who made the decision to end the publication and said it was the right decision because it wasn’t serving an academic purpose in the department and there weren’t enough students buying the yearbooks.

“I was really sad that we had to go to the point to discontinue it,” said Bacon. “I was really fond of the Prickly Pear and it was a valuable historical document for the university, but it didn’t meet an academic need for the department anymore.”

Bacon said yearbook sales at ACU and other colleges nationwide had been on the decline for about ten years when the decision to discontinue publication was made.

Bacon said that back in the 70s and 80s there were over 2,000 Prickly Pears sold every year but by the time they were going to discontinue the yearbook about only 350 were sold.

The problem was the cost and rise of social media, particularly Facebook, Bacon said.

“It allowed students to keep your pictures, and keep your stories, and the people they did it with and they saw that they didn’t need for the book.”

Many of the yearbook publishers also went out of business, including the one ACU used for the Prickly Pear. Bacon said the Journalism and Mass Communication department has no interest in taking the publication and she doesn’t think it can come back.

Cade White, journalism and mass communication instructor, was a faculty advisor for the last Prickly Pear.

White said the yearbook was operated in the JMC department and didn’t get much support from the university because the yearbook paid for itself and so did advertising.

“When we finally decided to stop making the book, we all knew that it would someday come back but we just didn’t know when or who’s power authority that would happen but I would say the biggest reason it died would be that it became cost prohibitive,” said White.

However, White said that schools that have never cut their yearbook was because “those schools usually were publishing their book not necessarily out of a journalism or communications department, it was usually a product of alumni or student life that it came from a different part of the university.”

“I don’t think there is a way for it to be successful again and I think the costs of bringing it back would be absolutely prohibitive,” said Bacon.

Although the future of bringing back the Prickly Pear looks dim, Kennedy said if the bill doesn’t pass it’s because of money, but she said she would still pursue a “digital way to document it.”