See also: Who works on Title IX cases: Meet the key players

Though Sherita Nickerson has hundreds of stories, she can’t tell them.

As deputy anti-harassment coordinator, Nickerson works every day with victims of sexual assault. Though her work is difficult and tedious, she’s passionate about helping people in crisis and chooses to do work she loves.

Nickerson’s job isn’t only difficult because of the weight of her duties, but also because she’s required to work through legal issues and ensuring the Title IX office remains compliant to federal law.

As the Title IX pendulum swings from gender equality to preventing sexual assault, the university’s Title IX office is required to navigate and work on internal resolutions to maintain compliance, though federal law puts borders on what a university can and cannot do.

Both the Title IX office, established in 2011, and ACUPD are required to work side-by-side in sexual assault reports, though more often than not, cases take separate routes. Because the burden of proof is higher in criminal investigations, most cases end up primarily as administrative investigations.

Since Betsy DeVos became Secretary of Education, universities around the nation have been working to think through how they will implement proposed Title IX guidelines once conversations have come to a close.

Though the tedious processes include a variety of challenges, administration meets victims with passion, a desire for campus education and hope for every person that walks into the Title IX office.

HISTORY

The “Dear Colleague” letter – Obama versus the Trump Administration

Since 2011, the Title IX policy has lived under the “Dear Colleague” letter guidelines, which prioritized a victim’s rights.

When DeVos took over, she changed the previous guidelines while interim guidelines continue to be altered.

After the new guidelines were proposed, a 60-day open comment period allowed the public to write concerns about the changes. Now, all comments are read through by the Department of Education, though Congress is joining in on the conversation.

Of over 105,000 comments, some are personal experiences, pleas against changing the guidelines and even insults toward DeVos. Though there is no official count of supporters versus critics, a majority of comments use a template to express concern.

Sexual harassment was defined as “unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature” under the Obama Administration, but DeVos proposed narrowing it to “unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature that is so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive that it effectively denies a person equal access to the recipient’s education program or activity.”

DeVos also proposed a live panel hearing in which both parties – the victim and the accused – question each other.

Under the “Dear Colleague” letter, university administrations were encouraged to finish an investigation within 60 days.

Nickerson said this was because there was fear or perception that an institution would allow a perpetrator, like a student-athlete, to continue at the university or finish their season.

Now, there is no guidance, but Nickerson said they try to stick with the 60-day timeframe. Over extended breaks, the process becomes more difficult because most people are no longer in Abilene.

“When you add all of that up, it could easily last three months,” Nickerson said.

In addition to outside factors, the more ongoing the cases, the longer each lasts.

ACUPD Police Chief Jimmy Ellison said in these situations, people tend to overly politicize these issues. Because of the pendulum swing from presidential administrations creating ambiguity in expectations, accused parties are now suing universities for lack of due process. Ellison said these cases are on the rise.

“A lot of the changes DeVos is proposing are based around the fact that there’s more and more civil litigation coming out of accused parties,” Ellison said.

ATIXA lands on campus

The university became part of the national organization called the Association of Title IX Administrators in 2012 after the “Dear Colleague” letter was distributed to college campuses across the nation to clarify the responsibilities of Title IX administrators.

In addition to becoming part of the association, the university updated its policy and began to train investigators and formalize a Title IX process and office. Nickerson was named deputy coordinator in 2014, and Ryan Bowman was added as a case manager in 2017.

Nickerson is able to look at questions and conversations from across the United States on a daily basis, and said she is reminded that these situations occur everywhere. Over 25,000 Title IX administrators participate in professional exchange and discuss practices for institutional compliance.

“That speaks volumes to how the institution is invested in Title IX,” Nickerson said. “It’s not necessarily a cheap investment, but the return can’t be calculated.”

PROCESS

Criminal investigations

Ellison said Title IX and ACUPD are two separate avenues that sometimes run together.

Some referrals go directly to the police, but more often than not, cases start at the Title IX office.

“This is because the university has done such a good job of getting Title IX well-known to the public. It’s become a household term,” Ellison said.

Where a case starts is determined by the police department assessing whether there is a crime involved. Ellison said often, there is a crime involved – assault, sexual assault or dating violence, stalking or harassment.

“We focus on whether there is criminal component,” Ellison said. “We are not, in any way, involved in the Title IX processes.”

Ellison said both ACUPD and the Abilene Police Department investigate criminal conduct, and alert the Title IX office that the crime may also have Title IX components which need to be assessed.

As an example of both offices working together, Ellison said in a sexual assault case, they want to minimize the number of times a victim has to tell their story. Other times, they work separately to address different components.

In criminal cases, ACUPD begins the investigation by taking the victims for a specialized medical examination within 96 hours of the assault.

Ellison said the process gets challenging if the police department has to ask the Title IX office to hold off temporarily, usually a few days, on starting administrative investigation process as they interview a suspect or gather critical, time-sensitive evidence. Nickerson’s team then assesses whether the request is feasible.

Statistically, victims of sexually-based crimes tend to drop the criminal charges but continue with their administrative complaint, Ellison said.

“When that happens, we are still conducting as much of an investigation as we can until the victim withdraws their case,” Ellison said.

The standard of proof in a criminal investigation is proof beyond a reasonable doubt, but in an administrative case, it is a preponderance of the evidence – is it more likely than not that something happened one way or the other.

Nickerson said they often call it “50 percent and a feather” because in many cases, there are no other witnesses besides the victim and the accused, making the case “he-said-she-said.”

“You’re really just trying to assess credibility in that feather,” said Wendy Jones, Title IX coordinator and chief human resources officer.

(Photo by Lauren Franco)

Nickerson said though accusers cannot go to jail based on Title IX investigations, they can be removed from the university.

On the other hand, if it is determined that there is enough evidence for law enforcement to proceed criminally, ACUPD or APD, depending on which agency is involved, presents the case to the district attorney’s office. The district attorney’s office considers whether they will move forward in a case.

More often than not, in sexual assault cases, the district attorney presents them to the grand jury, which reviews and decides whether the suspect will be indicted.

If indicted, the suspect stands trial for the criminal charge.

“It’s a long process, and it’s a slow process,” Ellison said. “In our world, people are so used to TV shows where the crime that occurs is investigated and resolved in a one-hour segment.”

Ellison said cases can sometimes last longer than a year depending on a variety of factors, and more time before a criminal case goes to trial. Investigations, however, are typically completed within three to four weeks.

“It’s challenging from an investigative perspective, it’s challenging from an administrative perspective, and it’s challenging from a spiritual perspective,” Ellison said. “We care about the choices these people are making, both suspects and victims. It’s tough work on both fronts.”

Nickerson said attorneys have said the relationship between ACUPD and the Title IX office is unique – the neighborly proximity of both offices and professional relationships make the tightrope easier to walk.

“We don’t always agree, but we do a fantastic job,” Ellison said. “We work together when we can and when it’s in the best interest of the victim, and separate our investigations in the interest of fairness and justice.”

Reporting to the Title IX office

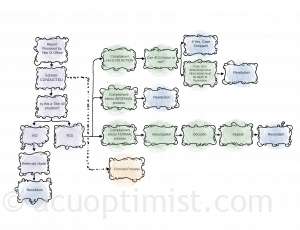

The first thing the Title IX office does is assess whether there are any criminal aspects, then begin to conduct administrative Title IX policy investigations.

Nickerson said sometimes they await a green light from Ellison, if it is necessary.

The Title IX policy, 18 pages long, is explained to the parties, and discusses how the process is governed.

“We would like to go through the policy, but you have to understand that when a victim or an accused party comes in, they’re typically so overwhelmed receiving so much information,” Nickerson said.

Ellison said people often mistake the Title IX office as a victim’s advocate, but that is not their role; they are solely investigators.

Nickerson agreed, explaining that her job is to conduct an impartial, thorough and fair investigation by receiving all of the facts.

“I can’t be biased toward the victim nor toward the accused,” Nickerson said. “That’s difficult.”

(Photo by Lauren Franco)

When a victim tells their story, it isn’t about believability, Nickerson said. Because of due process, the person being accused must be given a chance to tell their side of the story. This becomes difficult when no witnesses are present.

“We’re taking credibility assessments about what really happened that day,” Nickerson said. “We’re trained so we’re not just pulling things out of the sky.”

Title IX employees understand the neurobiology of trauma, trauma-influenced interviews, tonic immobilization and other things that are looked at from a professional standpoint.

“If you’re a victim, you want to be heard and be believed,” Nickerson said.

The victim is usually offered three ways to handle their complaint – do nothing, file an informal complaint or file a formal complaint.

Some victims chose to do nothing because they only want on file that something happened to them, so if the accuser’s name comes up again, there is a record of their history.

An informal resolution is a mediation between the two people who are accusing each other and being accused. Both parties discuss how they were affected and the mediator introduces conversations about boundaries and ways to move forward. There is no investigation.

A formal resolution includes an investigation. The victim and accused are asked who they would like to be a witness. After interviews, which can be captured by audio recording, body cameras or hand-written notes.

“We’re always trying to sharpen our process,” Nickerson said. “We want to make sure we’re the best we can when it comes to capturing information because these are people’s lives.”

During the investigation, both parties are encouraged to attend counseling, visit with their advocate or find support in some way.

Though they are encouraged to speak with their parents, most of the time, neither parties do, Nickerson said. Justifications are made in fear of repercussions by parents, like getting pulled out of school.

“We’re always pained by that because if parents knew you were going through such a traumatic ordeal, they would want to support you,” Nickerson said.

At the end of the investigation, Nickerson writes a findings report, usually including a credibility assessment, the part of the policy relevant to the accusation and her conclusion as to whether or not the policy was violated.

Jones receives the case next and reviews it to ensure no follow-ups are necessary. Then the case is given to one of four trained decision makers, each in administration. Decision makers receive the case without any prior knowledge of it and are not involved in the investigation.

Once a decision is made, it is shared with the two parties and both have the right to appeal. If a policy is violated, a sanction is given to the individual who violated the policy depending on the weight of the violation.

Most cases, Nickerson said, go through an appeals process – up to two rounds in which a decision can be upheld or overturned. After the second round, a case is closed.

A very low percentage of appeals are overturned, no more than 10 percent, Nickerson said.

“Every decision maker is objective, and confident they would appeal or overturn if they needed to, Jones said. “Right now, we’re at a place where we feel good about the investigations that we’re running and reports that we’re turning in. Title IX is just hard.”

Challenges

Ellison said often, it takes victims days to come forward. If someone is a victim of sexual assault, they should report immediately so that there is an opportunity to meet about options and capture evidence.

“It’s not pleasant to talk about, but if we don’t get the victim in a set period of time, we lose physical evidence that may help us tip the scale,” Ellison said.

Jones encouraged all victims of sexual assault to receive a rape kit, even if there is no intent to file charges immediately. By law, a person can be charged with sexual assault up to 10 years after the incident.

“If you do it, you don’t ever have to use it, but a year later, you can’t go back and take it,” Jones said.

Results of the rape kit are confidential and are for law enforcement and prosecution purposes only. They are not shared administratively with Title IX or with ACU.

Sometimes, victims are hesitant to come forward in fear of punishment for violating the Code of Conduct, but Nickerson said both victims and witnesses receive full immunity from activities such as sex outside of marriage or drinking underage.

“We don’t want victims to not come forward out of fear that it be found in violation of a code of conduct,” Nickerson said. “We try to make that known when we do our education.”

What’s public?

Jones said most victims want confidentiality in their case, so the lack of communication between the university and audiences is about respecting dignity and privacy.

(Photo by Lauren Franco)

In addition, though victims are alleging that something happened, all cases must be investigated first. Sometimes when a victim comes forward, they do not want to file charges nor a complaint, thus the public will not be notified.

None of the parties – ACUPD, APD nor the Title IX office – are able to talk about specific cases.

“When a victim withdraws their desire to file criminal charges, the law enforcement agency, whether it be ACUPD or APD, closes that case out. The case still exists, there’s still a folder and a case file, but it was closed at the request of the victim, therefore it never reached final adjudication, so it’s not eligible to be released to the media,” Ellison said.

Neither APD nor ACUPD issue press releases about the typical types of sexual assaults. If there were a pattern, or the general public was at ongoing risk from an unknown perpetrator, a press release would be issued through the university.

“In terms of the average victim coming in here and reporting a situation occurring within a relationship, there’s nothing about that that needs to be public,” Ellison said.

Even if an arrest is made, victims are not identified. Ellison said there are a lot of steps to ensure anonymity.

EDUCATION

The Kavanaugh and #MeToo effects

Ellison said sexual assault crimes are the most underreported crime, but because of the social climate and national attention, victims feel more empowered and believed.

“Those things coupled with the incredible resources that the university has dedicated to awareness, making it a household term on campus, of course we’re seeing a spike in reports,” Ellison said.

Despite the increase in reports, Ellison said the trend does not indicate an increase in activity. Still, statistics show that as many cases are received, two-to-three times as many may go unreported.

Jones said when Ellison came to campus in 2001 and started implementing education about crime in general, numbers spiked for other crimes.

“Over time when you’ve had enough history when we’ve got a number of people we’re working with, are we really seeing a true increase or are we leveling out because we’ve reached the masses in education,” Jones said. “Our process has not been in place long enough for us to have definitive answers statistically.”

The eyes and the ears from day one

Nickerson said institutions typically think there’s a spike in reports, but it isn’t because more instances are happening, but because education has gotten out and people feel more comfortable reporting.

When incoming students reach campus, they are required to participate in the Title IX awareness training, Everfi. Faculty and staff are also required to complete the course.

Everfi, a two-hour long training, introduces students to topics such as importance of values, aspects of (un)healthy relationships, gender socialization, sexual assault, consent, bystander intervention, survivor support and responding to student disclosures.

(Photo by Lauren Franco)

Ellison said anyone willing to give him, Nickerson and Jones an hour or less to talk about Title IX would benefit from a presentation about laws governing consent and harassment.

“I think we do a good job permeating the whole campus,” Ellison said.

Nickerson said though everybody cares, ACUPD, the Title IX office and administration want what’s best for the victim and accused.

“We know that we have tough work to do,” Nickerson said. “If an arrest has to occur, or an expulsion, ACUPD and Title IX still care about those people and want them to be successful. They have to be held accountable, but we have a genuine care and concern for this process, which is unique and a blessing.”